17 Linear regression

17.1 Objectives

Questions

- When should I use a linear regression?

- How do I interpret the results?

Objectives

- Be able to perform a linear regression in R

- Use ANOVA to check if the slope of the regression differs from zero

- Understand the underlying assumptions for linear regression analysis

- Use diagnostic plots to check these assumptions

17.2 Purpose and aim

Regression analysis not only tests for an association between two or more variables, but also allows one to investigate quantitatively the nature of any relationship which is present, and thus determine whether one variable may be used to predict values of another. Simple linear regression essentially models the dependence of a scalar dependent variable (y) on an independent (or explanatory) variable (x) according to the relationship:

\[\begin{equation*} y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x \end{equation*}\]

where \(\beta_0\) is the value of the intercept and \(\beta_1\) is the slope of the fitted line. The aim of simple linear regression analysis to assess whether the coefficient of the slope, \(\beta_1\), is actually different from zero. If it is different from zero then we can say that \(x\) has a significant effect on \(y\) (since changing \(x\) leads to a predicted change in \(y\)), whereas if it isn’t significantly different from zero, then we say that there isn’t sufficient evidence of a relationship. Of course, in order to assess whether the slope is significantly different from zero we first need to calculate the values of \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\).

17.4 Data and hypotheses

We will perform a simple linear regression analysis on the two variables murder and assault from the USArrests dataset. We wish to determine whether the assault variable is a significant predictor of the murder variable. This means that we will need to find the coefficients \(\beta_0\) and \(\beta_1\) that best fit the following macabre equation:

\[\begin{equation*} Murder = \beta_0 + \beta_1 \cdot Assault \end{equation*}\]

And then will be testing the following null and alternative hypotheses:

-

\(H_0\):

assaultis not a significant predictor ofmurder, \(\beta_1 = 0\) -

\(H_1\):

assaultis a significant predictor ofmurder, \(\beta_1 \neq 0\)

17.5 Summarise and visualise

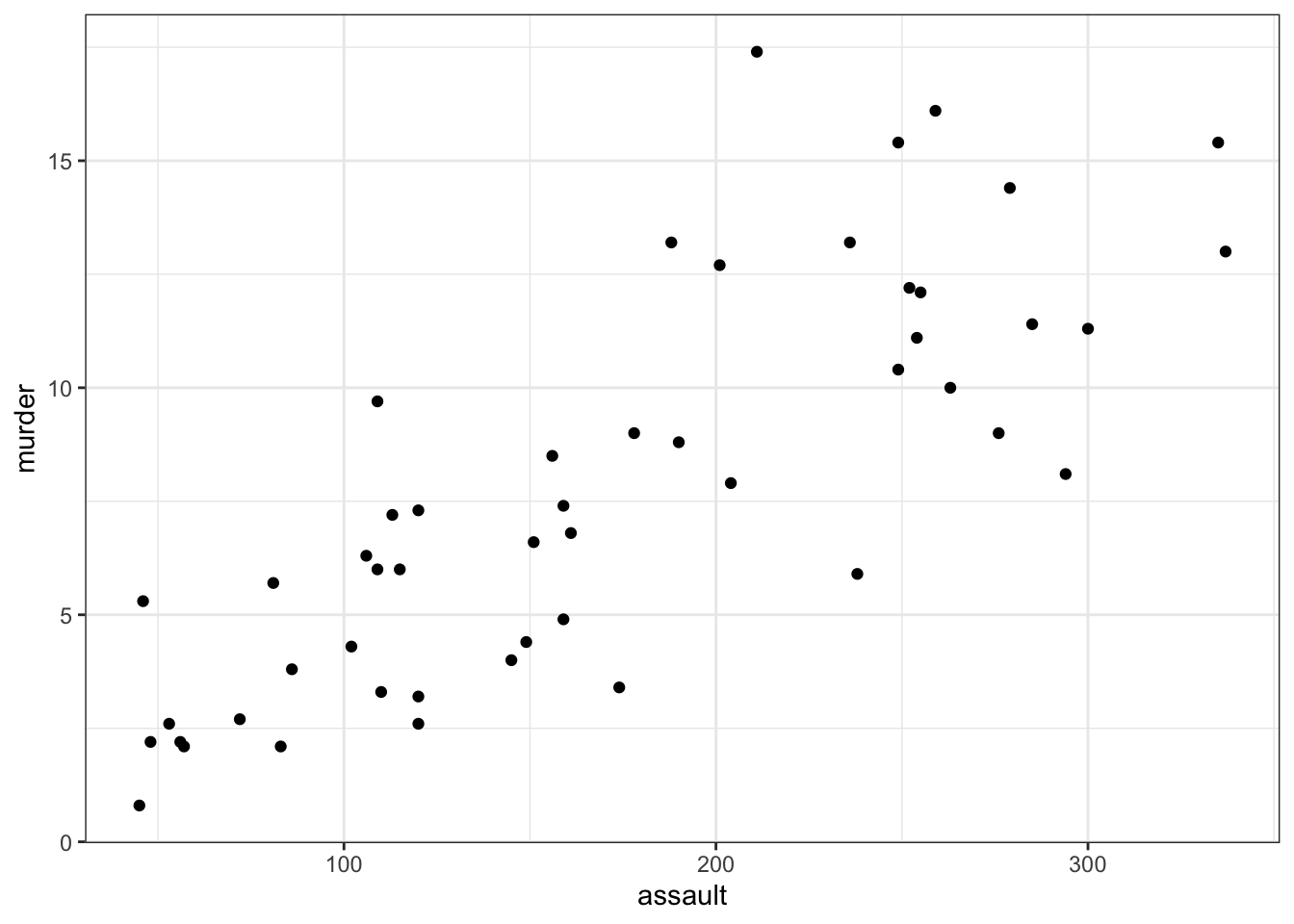

You can visualise the data with:

# create scatterplot of the data

USArrests %>%

ggplot(aes(x = assault, y = murder)) +

geom_point()

There appears to be a relatively strong positive relationship between these two variables and whilst there is a reasonable scatter of the points around any trend line, we would probably expect a significant result in this case.

17.6 Assumptions

In order for a linear regression analysis to be valid 4 key assumptions need to be met:

- The data must be linear (it is entirely possible to calculate a straight line through data that is not straight - it doesn’t mean that you should!)

- The residuals must be normally distributed

- The residuals must not be correlated with their fitted values

- The fit should not depend overly much on a single point (no point should have high leverage).

Whether these assumptions are met can easily be checked visually by producing four key diagnostic plots.

First we need to define the linear model:

lm_1 <- lm(murder ~ assault,

data = USArrests)- The first argument to

lmis a formula saying thatmurderdepends onassaults. As we have seen before, the syntax is generallydependent variable~independent variable. - The second argument specifies which dataset to use

Next, we can create diagnostic plots for the model:

lm_1 %>%

resid_panel(plots = c("resid", "qq", "ls", "cookd"),

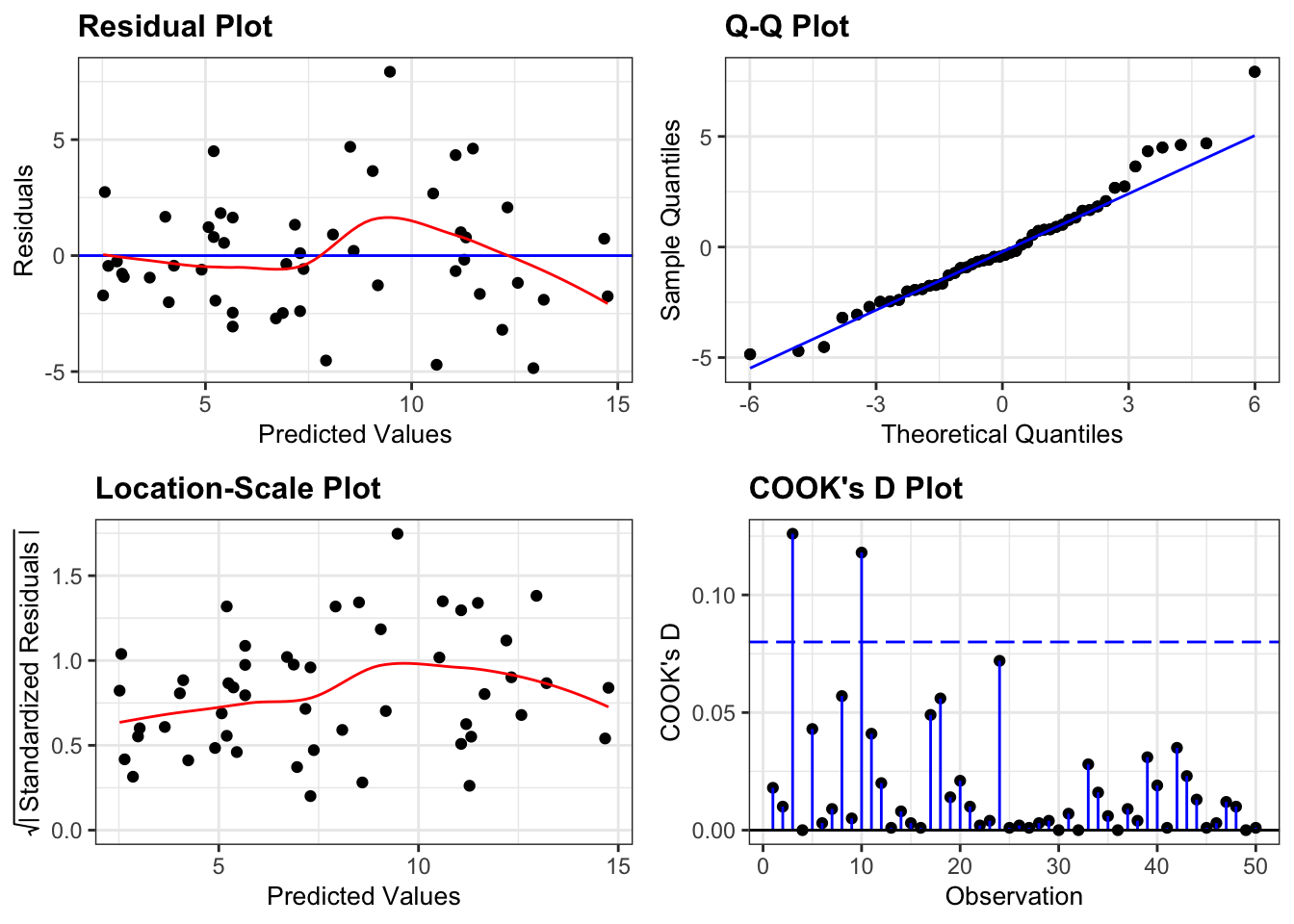

smoother = TRUE)

- The top left graph plots the Residuals plot. If the data are best explained by a straight line then there should be a uniform distribution of points above and below the horizontal blue line (and if there are sufficient points then the red line, which is a smoother line, should be on top of the blue line). This plot is pretty good.

- The top right graph shows the Q-Q plot which allows a visual inspection of normality. If the residuals are normally distributed, then the points should lie on the diagonal dotted line. This isn’t too bad but there is some slight snaking towards the upper end and there appears to be an outlier.

- The bottom left Location-scale graph allows us to investigate whether there is any correlation between the residuals and the predicted values and whether the variance of the residuals changes significantly. If not, then the red line should be horizontal. If there is any correlation or change in variance then the red line will not be horizontal. This plot is fine.

- The last graph shows the Cook’s distance and tests if any one point has an unnecessarily large effect on the fit. The important aspect here is to see if any points are larger than 0.5 (meaning you’d have to be careful) or 1.0 (meaning you’d definitely have to check if that point has an large effect on the model). If not, then no point has undue influence. This plot is good.

Formally, if there is any concern after looking at the diagnostic plots, then a linear regression is not valid. However, disappointingly, very few people ever check whether the linear regression assumptions have been met before quoting the results.

Let’s change this through leading by example!

17.7 Implement test

We have already defined the linear model, so we can have a closer look at it:

# show the linear model

lm_1##

## Call:

## lm(formula = murder ~ assault, data = USArrests)

##

## Coefficients:

## (Intercept) assault

## 0.63168 0.04191The function lm returns a linear model (lm) object which is essentially a list containing everything necessary to understand and analyse a linear model. However, if we just type the model name (as we have above) then it just prints to the screen the actual coefficients of the model i.e. the intercept and the slope of the line.

So here we have found that the line of best fit is given by:

\[\begin{equation*} Murder = 0.63 + 0.042 \cdot Assault \end{equation*}\]

Assess whether the slope is significantly different from zero:

anova(lm_1)Here, we again use the anova() command to assess significance. This shouldn’t be too surprising at this stage if the introductory lectures made any sense. From a mathematical perspective, one-way ANOVA and simple linear regression are exactly the same as each other and it makes sense that we should use the same command to analyse them in R.

17.8 Interpret output and report results

## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Response: murder

## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## assault 1 597.70 597.70 86.454 2.596e-12 ***

## Residuals 48 331.85 6.91

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1This is exactly the same format as the table we saw for one-way ANOVA:

- The 1st line just tells you the that this is an ANOVA test

- The 2nd line tells you what the response variable is (in this case

Murder) - The 3rd, 4th and 5th lines are an ANOVA table which contain some useful values:

- The

Dfcolumn contains the degrees of freedom values on each row, 1 and 48 (which we’ll need for the reporting) - The

Fvalue column contains the F statistic, 86.454 (which again we’ll need for reporting). - The p-value is 2.596e-12 and is the number directly under the

Pr(>F)on the 4th line. - The other values in the table (in the

Sum SqandMean Sq) column are used to calculate the F statistic itself and we don’t need to know these.

- The

Again, the p-value is what we’re most interested in here and shows us the probability of getting data such as ours if the null hypothesis were actually true and the slope of the line were actually zero. Since the p-value is excruciatingly tiny we can reject our null hypothesis and state that:

A simple linear regression showed that the assault rate in US states was a significant predictor of the number of murders (F = 86.45, df = 1,48, p = 2.59x10-12).

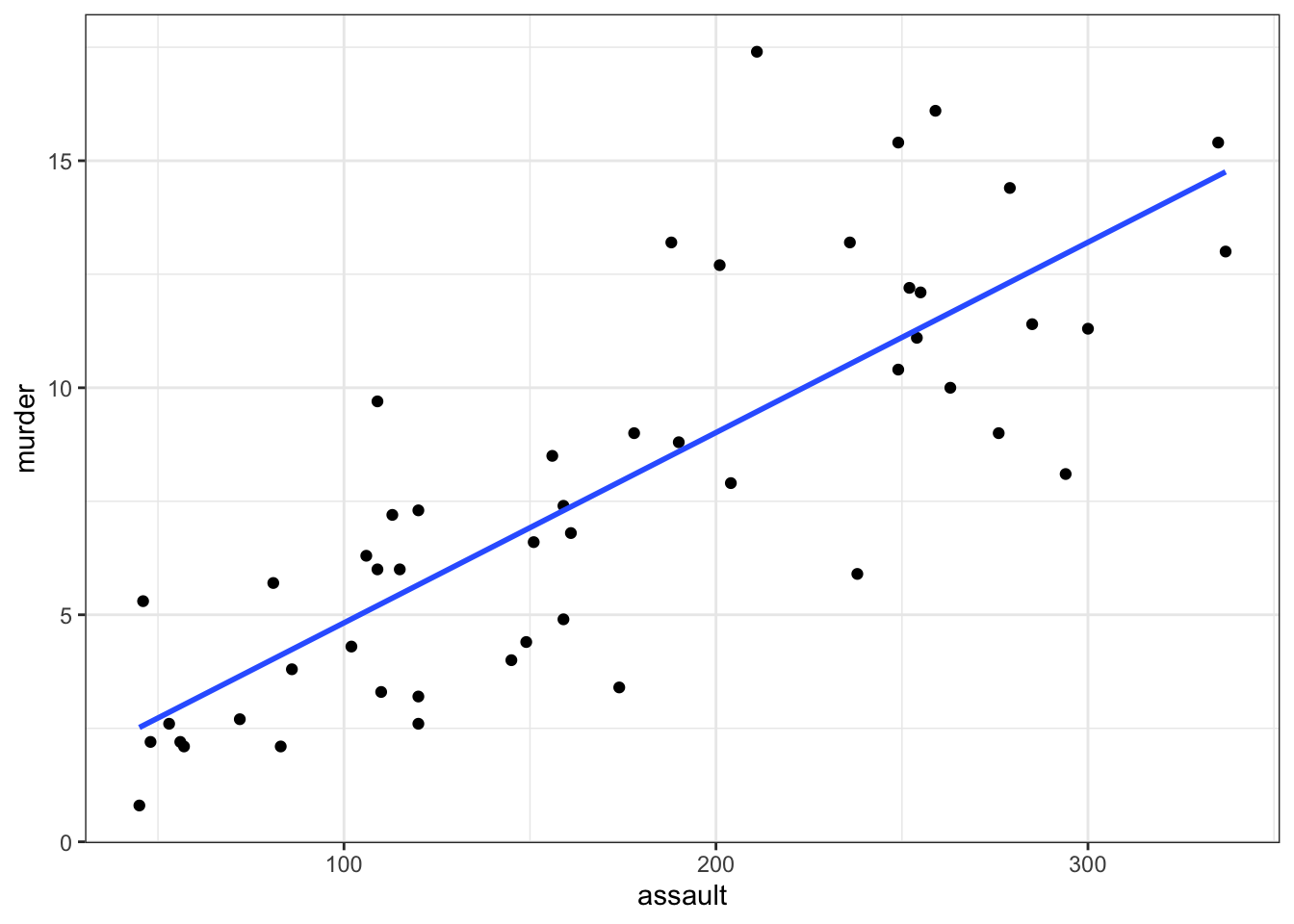

Plotting the regression line

It can be very helpful to plot the regression line with the original data to see how far the data are from the predicted linear values. We can do this with:

# plot the data

USArrests %>%

ggplot(aes(x = assault, y = murder)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

- We plot all the data using

geom_point() - Next, we add the linear model using

geom_smooth(method = "lm"), hiding the confidence intervals (se = FALSE)

17.9 Exercise

Exercise 17.1 Linear regression

Calculate two simple linear regressions using the data/tidy/CS3-statedata.csv dataset, first for the variable life_exp on the variable murder and then for the variable hs_grad on frost.

Do the following in both cases:

- Find the value of the slope and intercept coefficients for both regressions

- Determine if the slope is significantly different from zero (i.e. is there a relationship between the two variables)

- Produce a scatter plot of the data with the line of best fit superimposed on top.

- Produce diagnostic plots and discuss with your (virtual) neighbour if you should have carried out a simple linear regression in each case

Answer

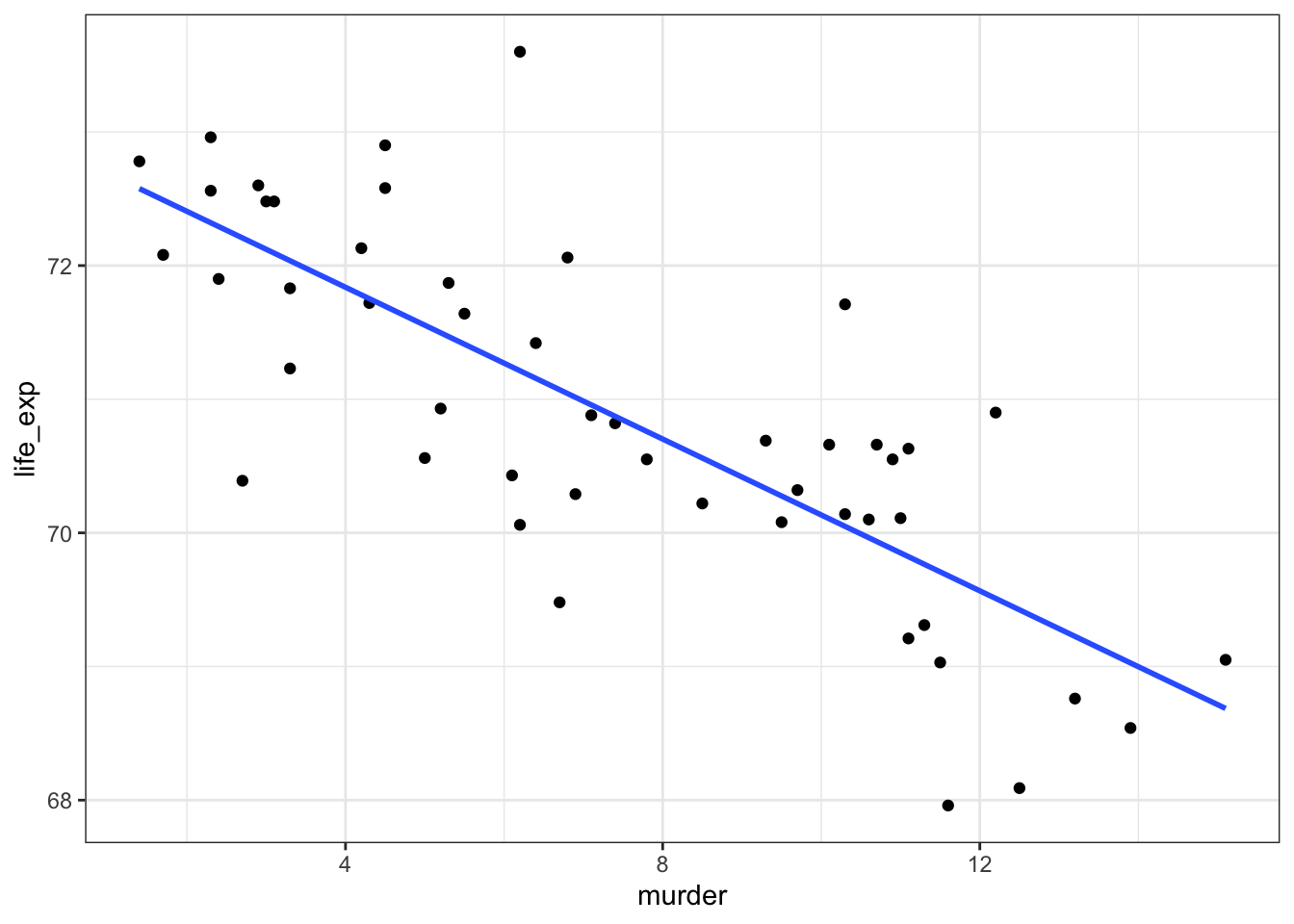

Murder and Life Expectancy

Let’s see if the murder variable can be used to predict the life_exp variable. Let’s plot it first of all.

# plot the data and add the regression line

USAstate %>%

ggplot(aes(x = murder, y = life_exp)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

We visualise for the same reasons:

- We check that the data aren’t obviously wrong. Here we have sensible values for life expectancy (nothing massively large or small), and plausible values for murder rates (not that I’m that au fait with US murder rates in 1976 but small positive numbers seem plausible).

- We check to see what we would expect from the statistical analysis. Here there does appear to be a reasonable downward trend to the data. I would be surprised if we didn’t get a significant result given the amount of data and the spread of the data about the line

- We check the assumptions (only roughly though as we’ll be doing this properly in a minute). Nothing immediately gives me cause for concern; the data appear linear, the spread of the data around the line appears homogeneous and symmetrical. No outliers either.

Now, let’s check the assumptions with the diagnostic plots.

# create a linear model

lm_murder <- lm(life_exp ~ murder,

data = USAstate)

# create the diagnostic plots

lm_murder %>%

resid_panel(plots = c("resid", "qq", "ls", "cookd"),

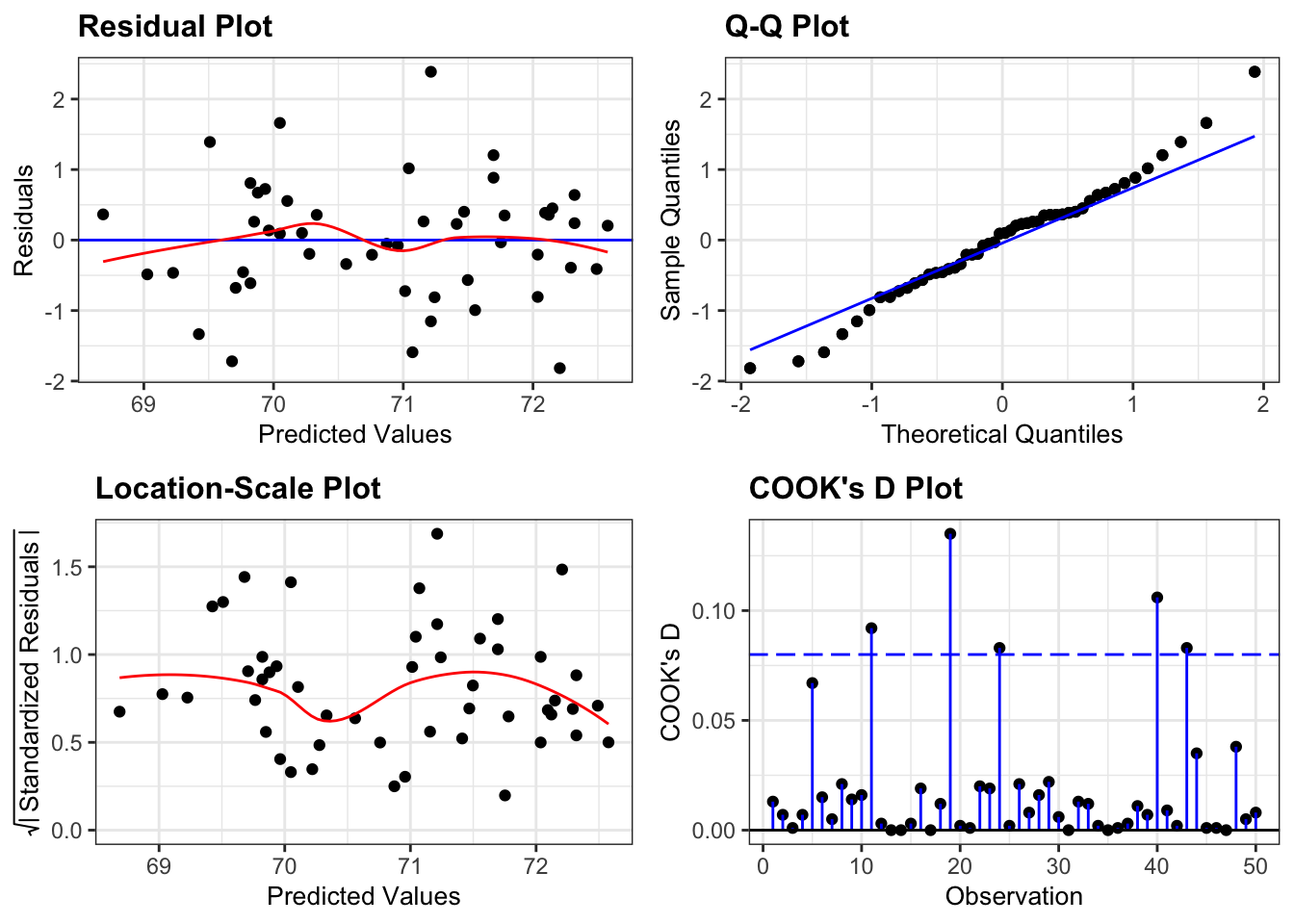

smoother = TRUE)

The Residuals plot appears symmetric enough (similar distribution of points above and below the horizontal blue line) for me to happy with linearity. Similarly the red line in the Location-Scale plot looks horizontal enough for me to be happy with homogeneity of variance. There aren’t any influential points in the Cook’s distance plot. The only plot that does give me a bit of concern is the Q-Q plot. Here we see clear evidence of snaking, although the degree of snaking isn’t actually that bad. This just means that we can be pretty certain that the distribution of residuals isn’t normal, but also that it isn’t very non-normal. What do we do in this situation? Well, there are three possible options:

- Appeal to the Central Limit Theorem. This states that if we have a large enough sample size we don’t have to worry about whether the distribution of the residuals are normally distributed. Large enough is a bit of a moving target here and to be honest it depends on how non-normal the underlying data are. If the data are only a little bit non-normal then we can get away with using a smaller sample than if the data are massively skewed (for example). This is not an exact science, but anything over 30 data points is considered a lot for mild to moderate non-normality (as we have in this case). If the data were very skewed then we would be looking for more data points (50-100). So, for this example we can legitimately just carry on with our analysis without worrying.

- Try transforming the data. Here we would try applying some mathematical functions to the response variable (

life_exp) in the hope that repeating the analysis with this transformed variable would make things better. To be honest with you it might not work and we won’t know until we try. Dealing with transformed variables is legitimate as an approach but it can make interpreting the model a bit more challenging. In this particular example none of the traditional transformations (log, square-root, reciprocal) do anything to fix the slight lack of normality (you can take my word for it or you could try it using;lm(log(LifeExp ~ Murder, data = USAstate))for example. - Go with permutation methods / bootstrapping. This approach would definitely work. I don’t have time to explain it here (it’s the subject of an entire other practical). This approach also requires us to have a reasonably large sample size to work well as we have to assume that the distribution of the sample is a good approximation for the distribution of the entire dataset.

So in this case, because we have a large enough sample size and our deviation from normality isn’t too bad, we can just crack on with the standard analysis.

So, let’s actually do the analysis:

anova(lm_murder)## Analysis of Variance Table

##

## Response: life_exp

## Df Sum Sq Mean Sq F value Pr(>F)

## murder 1 53.838 53.838 74.989 2.26e-11 ***

## Residuals 48 34.461 0.718

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1And after all of that we find that the murder rate is a statistically significant predictor of life expectancy in US states. Woohoo!

High School Graduation and Frosty Days

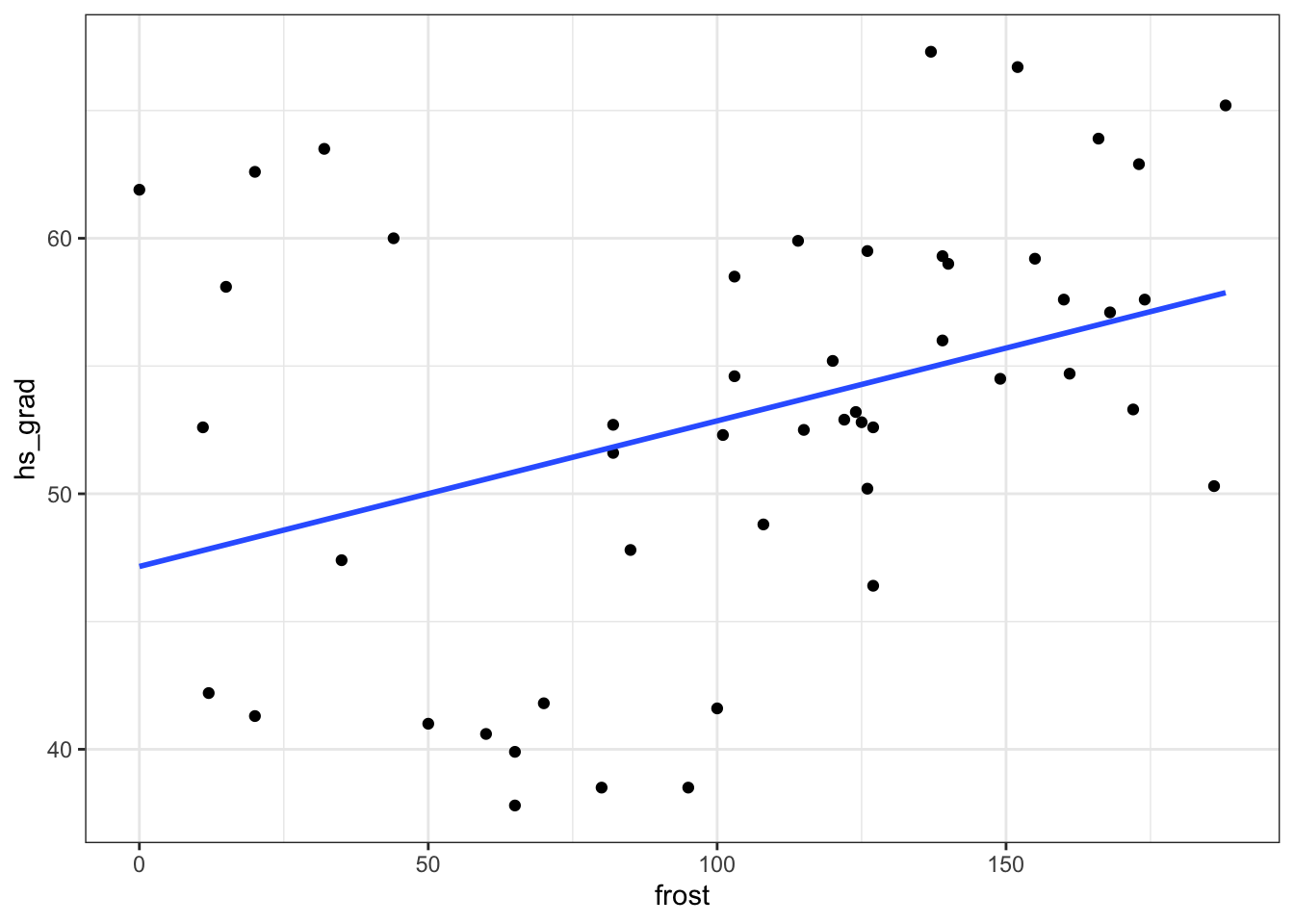

Now let’s investigate the relationship between the proportion of High School Graduates a state has (hs_grad) and the mean number of days below freezing (frost) within each state.

# plot the data

USAstate %>%

ggplot(aes(x = frost, y = hs_grad)) +

geom_point() +

geom_smooth(method = "lm", se = FALSE)

Once again, we look at the data.

- There doesn’t appear to be any ridiculous errors with the data; High School graduation proportions are in the 0-100% range and the mean number of sub-zero days for each state are between 0 and 365, so these numbers are plausible.

- Whilst there is a trend upwards, which wouldn’t surprise me if it came back as being significant, I’m a bit concerned about…

- The assumptions. I’m mainly concerned that the data aren’t very linear. There appears to be a noticeable pattern to the data with some sort of minimum around 50-60 Frost days. This means that it’s hard to assess the other assumptions.

Let’s check these out properly

Now, let’s check the assumptions with the diagnostic plots.

# create a linear model

lm_frost <- lm(hs_grad ~ frost,

data = USAstate)

# create the diagnostic plots

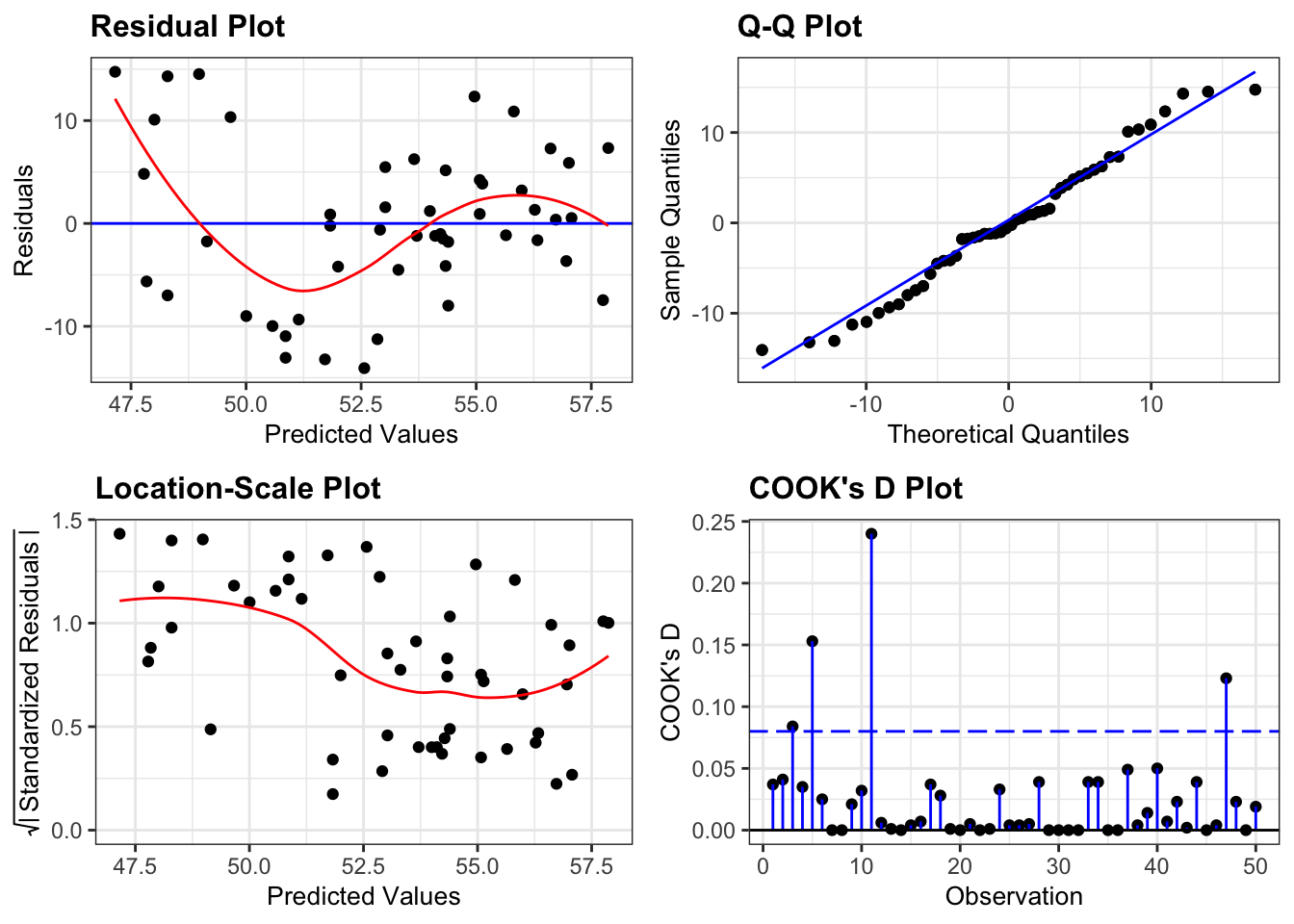

lm_frost %>%

resid_panel(plots = c("resid", "qq", "ls", "cookd"),

smoother = TRUE)

We can see that what we suspected from before is backed up by the Residuals plot. The data aren’t linear and there appears to be some sort of odd down-up pattern here. Given the lack of linearity it just isn’t worth worrying about the other plots because our model is misspecified: a straight line just doesn’t represent our data at all.

Just for reference, and as practice for looking at diagnostic plots, if we ignore the lack of linearity then we can say that

- Normality is pretty good from the Q-Q plot

- Homogeneity of variance isn’t very good and there appears to be a noticeable drop in variance as we go from left to right (from consideration of the Location-Scale plot)

- There don’t appear to be any influential points (by looking at the Cook’s distance plot)

However, none of that is relevant in this particular case since the data aren’t linear and a straight line would be the wrong model to fit.

So what do we do in this situation?

Well actually, this is a bit tricky as there aren’t any easy fixes here. There are two broad solutions for dealing with a misspecified model.

- The most common solution is that we need more predictor variables in the model. Here we’re trying to explain/predict high school graduation only using the number of frost days. Obviously there are many more things that would affect the proportion of high school graduates than just how cold it is in a State (which is a weird potential predictor when you think about it) and so what we would need is a statistical approach that allows us to look at multiple predictor variables. We’ll cover that approach in the next two sessions.

- The other potential solution is to say that high school graduation can in fact be predicted only by the number of frost days but that the relationship between them isn’t linear. We would then need to specify a relationship (a curve basically) and then try to fit the data to the new, non-linear, curve. This process is called, unsurprisingly, non-linear regression and we don’t cover that in this course. This process is best used when there is already a strong theoretical reason for a non-linear relationship between two variables (such as sigmoidal dose-response curves in pharmacology or exponential relationships in cell growth). In this case we don’t have any such preconceived notions and so it wouldn’t really be appropriate in this case.

Neither of these solutions can be tackled with the knowledge that we have so far in the course but we can definitely say that based upon this data set, there isn’t a linear relationship (significant or otherwise) between frosty days and high school graduation rates.

17.10 Key points

- Linear regression tests if a linear relationship exists between two or more variables

- If so, we can use one variable to predict another

- A linear model has an intercept and slope and we test if the slope differs from zero

- We create linear models in R with the

lm()function and useanova()to assess the slope coefficient - We can only use a linear regression if these four assumptions are met:

- The data are linear

- Residuals are normally distributed

- Residuals are not correlated with their fitted values

- No single point should have a large influence on the linear model

- We can use

resid_panel()to get diagnostic plots in R, which help evaluate these assumptions